March

22, 1973 - San Carlos, California

I

turned around in my front row seat to watch Marlene Dietrich scurrying

down the aisle past me, generating a baby blue vortex of Chanel-scented

air as she sprinted toward the unlit stage of the Circle Star Theatre.

Glancing over her shoulder to memorize her route she noticed me sitting

there alone, an audience of one in a two thousand-seat theatre, then

continued

down the aisle counting to herself with each step. Rehearsal had begun.

“Twenty-two,

twenty-thwee, twenty-four...” she muttered and then, looking straight

forward,

head tilted up, she used the golden tips of her sequined high heels to

feel out the three steps leading to the circular stage. She raised

herself

up so gracefully it was as though some invisible hand was lifting her

and

gently placing her back down. She was rehearsing her entrance down the

steeply raked aisle and feeling out the steps for that evening’s

opening.

As long as she was there, she'd sing a couple of songs.

I was

startled - though I'm easily startled - because A) I had just smoked a

joint with her stage manager in the alley next to the theatre (Yes, it

was the seventies) and B) I was assured that Dietrich never attended

orchestra

rehearsals; certainly never on her opening night; and if she did

attend,

she never, ever sang.

Dressed

in a light blue denim pantsuit with wide bell-bottoms and tightly

tailored

jacket, her outfit was topped by an enormous denim Dutch boy cap

perched

upon unkempt tangles of ash blonde hair. With pie-plate sized

sunglasses

obscuring her eyes, she was heading straight for the microphone. The

sparkling

golden shoes were anachronistic to her blue jean ensemble but the

three-inch

heels were the ones she would be wearing for the performance that

evening

and she needed to be sure of her footing. She was not happy.

Stan

Freeman, her musical director and my best friend, was conducting the

orchestra

and had just begun the introduction to “Where Have All The Flowers

Gone?”

which Dietrich sang as an anti-Viet Nam War protest. Stanley was

looking

at his music when she glided unseen onto the stage behind him and he

jumped

a foot when she started to bark out orders. A few of the musicians

tapped

their instruments as a way of acknowledging her presence but she either

didn't notice or didn't care. The music continued.

“Get

me a wamp! I need a wamp! I can't climb steps with a spotlight in my

eyes.

I WANT A WAMP!” It dawned on the stoned-out stage manager that he was

responsible

for satisfying such a request and began darting around trying to locate

a “wamp” as the work lights suddenly popped on. Although the stage

would

revolve a complete 360 degrees for her performance, it was stationary

for

now. The great Dietrich faced me as she grabbed the microphone and

caught

up to the song, joining in on “…long time passing…Where have all the

flowers

gone, long time ago?”

Without

makeup, standing under stark work lights that bleached the color from

her

hat, her clothes and the lines from her face, she was transformed into

a black and white image. I felt as though I was watching an early film

of Dietrich and not a live person. She was mesmerizing. There was

something

so compelling about her presence that you appreciated why she had

departed

the rank of movie star and had arrived at living legend.

I was

so taken by the sight of her that I almost forgot how cold it was in

the

domed cavern - what seemed a few degrees above freezing. Dietrich told

us all in the limo on the ride out that she wanted the air to be

glacial

so that the audience would remain alert. At this temperature, they

would

congeal. Standing at the mike, she was singing full out,

“Where have all the graveyards gone long time passing?"

"Where have all the graveyards gone long time ago?” in a low rumbling

monotone

that made her sound more like an ancient monk chanting than a chanteuse.

Suddenly

she stopped. “Whewe are de bullets? Wemember de bullets!” she

admonished

Stanley.

“I’ll make sure they’re louder, Marlene,” bellowed Stan as he abruptly

waved the orchestra to a stop. “At numbers 78 and 79, those violins are

fortissimo and multi-pizzicato. They should sound like gunshots.”

“And bullets!” added Dietrich.

The

orchestra began again and the violins pierced the air with their

staccato

shrapnel stings as Dietrich sang on to the end of Pete Seeger‘s

masterpiece.

She

stepped back from the mike as Stan told the orchestra that the next

song

was, unlike Dietrich’s current mood, bouncy and whimsical. It was

Charles

Marrowood‘s Australian novelty number, “Boomerang Baby.” Stan started

the

slinky vamp and Dietrich purred into the mike,

“Boom boom boom boom boom-a-wang, baby.

Fly, fly away, fly away from me, you boom-a-wang baby.”

When

she got to the spoken bridge of the song, she took off those enormous

sunglasses

and looked me right in the eye, “Hey there. Back so soon? Have a nice

twip?”

She finished the song and asked again, to no one in particular, “Whewe

is my wamp?”

The

stage manager, still too stoned to move quickly, sauntered down the

aisle

and assured Marlene that a ramp was being taken out of storage and

would

be in place within fifteen minutes.

“I will not be lied to,” she said with sharp finality.

Muttering

something to the effect of “Everybody lies to you,” the worker set off

again to look for a “wamp.” I recalled a story Stan told me about

conducting

for Dietrich during her Tokyo engagement at the Imperial Hotel when a

concertmaster's

lie very nearly led to an International incident.

The

Japanese rehearsal was to begin at one p.m. By one-thirty, only half of

the local Tokyo musicians had arrived and Dietrich asked where the

other

half were and why they were so late? It was “un-pwofessional! “

The

concertmaster, bowing excessively low, indicated to Miss Dietrich that

the string section was stuck in a massive traffic jam near the Ginza

and

would arrive at the venue shortly. Dietrich thought it a was strange

explanation

and asked a very logical question, “Do they all dwive here together in

one car?” The concertmaster responded with another plastic smile,

more excessive bow and backed away from her without further comment.

Ten

minutes more went by when Dietrich encountered the first violinist and

asked him where the other musicians were?

“They called in sick,” he told her, “and the producers were finding

substitutes.”

Another bow.

Stan

reported that Dietrich went ballistic. She drove her foot through the

floorboard

of political correctness and shattered it by saying, “Stop! I have now

been told two diffewent stowies. First, the musicians are delayed by

twaffic

and now you tell me they are all sick. This is not acceptable. You have

pwoven to me once and for all that the Japanese are sneaking, thieving,

lying little people and I have not forgotten Pearl Harbor!” Marlene was

not going to get the Ambassadorship to Tokyo that year.

Stan

said there was a party for her after the opening show given by the

Mayor

of Tokyo where extravagant golden-silk kimonos had been made especially

to present to her as gifts. She was so upset by the lies she had been

told

that refused to attend and sent word to the Mayor “to take back his

bathwobes!”

I was

snapped out of my daydream by a change of lighting. Some techies

noticed

Dietrich on the stage, turned out the house lights, brought the stage

lights

up and a phenomenon occurred. She seemed to get taller in the light,

like

a flower responding to the sun as she let them warm and comfort her.

She

stepped back and listened for the introduction to the next song. It was

"I Wish You Love.”

I wondered

why I had smoked that joint with the stage manager outside in the alley

before rehearsals began. Was I appreciating the full impact of this

event?

Well, it was 1973 and everyone smoked pot for breakfast with their

coffee

and I thought the music would sound enhanced. The fact that Dietrich

herself

was singing to me alone in the middle of this icy cavern was by far the

most surrealistic experience of my life to date. Or was it?

Was

it my father dating Joan Crawford? Or being invited to Fenwick by Kate

Hepburn? Or the New York City blackout of 1965? Or working with Ethel

Merman?

Or riding to New York's City Hall with Mayor John Lindsay? Or

campaigning

with Harvey Milk in San Francisco? Or hiring a 16 year-old John

Travolta

to be in a New Jersey dinner theatre production of “Bye Bye Birdie?” Or

meeting President Kennedy? Or Mrs. Roosevelt?

No,

this moment with Dietrich was it. Especially as she stopped singing in

the middle of the song when she saw that a ramp had just been exchanged

for the three steps and Dietrich seemed eager to try it out. She hit

the

aisle and just as she passed me said, “The Fisherman” and kept on

going.

It sounded like code - something one spy would say to another before

exposing

all their secrets.

“The

Fishermam.” She didn't really stop. She didn't really look directly at

me. Yet I knew she was speaking to me and wanted a response. But I was

still too stoned to comprehend her meaning or form a response.

“The

Fisherman.” What did it all mean? Was there a clandestine operation

going

on?

I thought

about Myron Cohen’s joke about the Jewish spy on his first day at the

job.

He's given the most dangerous and critical assignment in the history of

the CIA. He is to go to an address, ring the doorbell marked “GOLDBERG”

and when a man comes to the door say the code: “The Sun Is Shining.” He

will then be given confidential documents that will save the world. If

anything goes wrong he is to bite down on a cyanide capsule placed

under

his tongue. At all costs, this mission must be kept top secret.

Our

new spy gets to the address and sees two names and two buzzers: A.

GOLDBERG

(1-A) and R. GOLDBERG (2-A). He rings the first bell and an elderly man

comes to the door. The new spy says, “The sun is shining.“ The old man

says “You want Goldberg, the Spy - Upstairs. So Dietrich is the spy and

“The Fisherman” is the code. Jeez, that pot was good.

After

the rehearsal, Stan told me that she had invited everyone in her party

out to a restaurant in San Francisco called The Fisherman for dinner

after

that evening’s show. Since I was with him, I was part of the group. The

show would start in four hours and since we were an hour drive from San

Francisco, we brought a change of clothes and would shower in the

dressing

room. Stanley thought that Dietrich was in a particularly good mood

since

she had deigned to come to the rehearsal.

“She

wanted to try out her wamp,” I explained, “and she decided to stay. She

saw me sitting there and wanted to do it just for me.” Stanley laughed

- God what an easy and wonderful laugher he was. His voice was like

stone

workers sifting through a gravel pit but when he laughed, his eyes

completely

shut and a rumble of contagious guffaws burst forth.

When

I went to San Francisco with him for this engagement, we had been

friends

for four years, having met through my roommate at the time, Bob Nigro,

who directed the long-gone NBC soap opera, “Search For Tomorrow.” Bobby

was another great laugher with a hairline trigger for high tone giggles

that lasted forever. One of the greatest laughs the three of us ever

had

was at Bobby’s expense.

We

were at Stan's house on Fire Island when Bobby walked directly into a

closed

floor-to-ceiling plate-glass door and knocked himself unconscious.

Stanley

and I were still hysterical when he came around. We weren't being mean.

Bobby had commented not an hour before that only a idiot couldn't tell

the difference between that door being opened and being closed.

The

forty-five minute trip from San Francisco to San Carlos was taken in a

stretch limo with the passengers being Miss Dietrich, Stanley, myself,

Jeanette (Marlene’s aide de camp), Gene (her drummer) and Gene’s wife,

who was also one of Marlene’s helpers. It was a stretch limo that

featured

jump seats and could hold five comfortably. Marlene opted to sit up

front

with the driver and leave the six of us fighting over the five seats.

Jeanette

met us at the top of the aisle and told us that Marlene was taking a

nap

but she would see us all at seven-thirty for cocktails. Stan said La

Dietrich

always had a few people in her dressing room an hour before the show

and

served champagne, which she never took herself. It was all part of the

ritual.

We

stayed in Stan’s dressing room with Chinese take-out until it was time

to change and go to Marlene’s. The drummer and his wife were there

already

along with Joe Davies (her British lighting designer), Jeff (the stoned

stage manager), the owner of the theatre and his wife and a silent,

dazed-looking

girl who just stood there without any seeming affiliation.

We

thought Marlene was in the other room of her dressing room suite, but

then

Jeanette came in from the hallway, followed by Marlene who had changed

into a bright red tailored pantsuit, white blouse and red fedora.

“Well,

it looks like a pawty,“ she said, “But what is a pawty without

champagne.“

The theatre owner signaled the silent girl who went to the hallway and

returned with a liquor trolley. Jeanette had already opened the door to

the inner room and from where I sat, I could see Marlene’s famous nude

dress in the mirror. It looked like it was standing up by itself.

Marlene,

looking older than her 70+ years, hung on the door of the inner

room

for a moment with a knowing smile on her face. She looked like a

magician about to enter the enchanted box, and only she held the secret

of the trick. The dressing room door closed and the old woman

disappeared.

Remember

Houdini’s great illusion, The Metamorphosis? He would lock his

assistant

in a trunk upon which he would then stand. A curtain flew up, then down

and in an instant they changed places and Houdini emerged from the

trunk

in a totally different costume. Forty-five minutes later, when

Dietrich‘s

dressing room door opened and she stepped back into the room, she had

been

completely transformed into the icon-legend-megastar of the Silver

Screen.

She was breathtaking. None of us could speak as we all took her in.

Then

she broke the ice. “Anybody have a banana?”

Speaking

of magic tricks, Jeanette seemed to pull a banana out of thin air and

handed

it to Marlene who carefully pulled the skin back and admired it before

taking a bite off the end.

I asked,

“Do you always have a banana before a show, Marlene?”

“Always!” she told me. “Potassium!“ And I’ll have another at

intermission.

It’s good for when you have to stand so long.”

“Fifteen minutes, Miss Dietrich!” announced Jeff, the Stage Manager.

Joe

Davies raised his champagne, “To our Marlene!”

I wondered

if I should join in the toast. After all, I had only met her the day

before

at the airport and wasn’t sure if I knew her well enough to enjoin with

the others to drink to “Our Marlene.” But I lifted my glass. “To Our

Marlene!”

After all, she was everyone’s Marlene.

As

soon as the toast was done, Jeanette opened the door to escort us out.

Marlene turned to the mirror and began to study every inch of herself

as

the door closed like a wipe fading out on a scene from one of her old

movies.

We stepped through the curtain into the back of the arena, which was

packed

and buzzing with anticipation.

I walked

down the same aisle I saw Dietrich stroll down that afternoon and I

started

counting my steps. I stopped at twenty-four. It was twenty-eight steps

to the ramp. I sat in the second row with Joe Davies, the designer who

created the magical lighting that kept her looking like a Rembrandt for

two hours.

Stanley

came down the aisle in his tuxedo, unannounced and unlit. He was

wearing

a new toupee. It was a little too big for his head. I had noticed at

the

orchestra rehearsal that his hair had seemed to have edema. It was at

least

twice as big as it had been when he woke up that morning. His

appointment

to get a “haircut” had been actually to get a new hairpiece that was

styled

with bangs and wings that reminded me of Imogene Coca. This one was so

over-sized you could, as they say, “Get to Baghdad on that rug!” The

day

after Dietrich opened at the Circle Star, the review in the San

Francisco

Chronicle was a rave except they reported that “Miss Dietrich’s

conductor

looked like Peter Lorre with a bad toupee.”

When

Stan was in place on the stage, the house lights went out, the audience

fluttered and a spotlight cut through the dark from one side of the

arena

to the other.

“Ladies

and gentlemen, the one and only, Marlene Dietrich.” Stan raised his

hand

and the orchestra came to life with the horns trumpeting the first

notes

of “Falling In Love Again” much like heralders announcing the arrival

of

a queen.

Wearing

that incredible white ermine coat which followed behind her, she

stepped

into her beam and floated down the aisle, looking straight forward,

neither

waiving to the cheering crowd nor acknowledging the standing ovation

they

were giving her. Head high, moving forward, I applauded her and

chuckled

to myself that I was the only one there who knew what was going on in

her

head - she was counting the steps.

On

the twenty-eighth step she started to ascend the “wamp” and the crowd

exploded.

She walked the perimeter of the circular stage so that everyone, as

Ethel

Mertz might say, could get a load of her. She acknowledged Stanley and

stepped to the mike and purred into it as if it were the ear of her

great

paramour.

“I can't give you anything but love, baby.

That's the only thing I've plenty of, baby…”

After

two more songs, the coat came off, the stage turned, she sang two dozen

more songs including “Lili Marlene” and “Falling In Love Again” and

left

them wanting more. The audience stood and screamed.

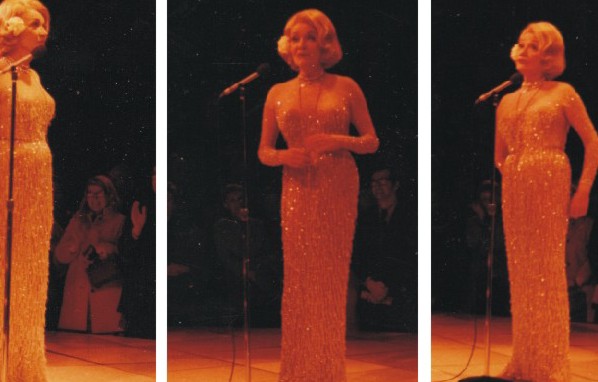

Stan Freeman

bows with Marlene Dietrich at the Queens Theatre, London (1972)

I had

seen this same show twice before Stan and I ever met. Once was in

Montreal

during Expo ‘67 and also when she played the Lunt-Fontanne on Broadway.

I took my cousin Eileen Quain to see it and she begged me to wait with

her so we could get Dietrich’s autograph after the show. We stood

outside

the stage door in three degree weather, right next to the door, and

when

Dietrich came out my cousin thrust her program at her,

“Miss Dietrich, may I please have your autograph?” implored Eileen.

Without

even looking at her Dietrich said “No“ and pushed her way through the

crowd

to her waiting limo. Oh, well. Five years later, I wanted to call

Eileen

and tell her I was sitting with Dietrich in her dressing room after her

show drinking champagne with her but she wouldn’t believe me. I hardly

believed it myself.

“I’m vewy hungwy,” said Marlene, who had now switched to vodka. “We’re

going to the Fisherman. I have a cwaving for soft-shelled cwabs.”

Stanley

bellowed, “How about you, Jim? Some soft shelled crabs and then

scallops

and maybe shrimp cocktail, lobster and shad roe? How does that sound?”

I raised

my glass and returned his toast by sticking out my tongue at him, which

Marlene caught.

“What’s this?”

Stan

explained that he was kidding me because I had an aversion to fish. I

couldn’t

stand the sight of it. Still can’t. I tried to eat tuna salad once and

couldn’t actually come to put it in my mouth before I started gagging.

I know it’s totally psychological. I know it’s totally

irrational.

know I’m depriving myself of some of the greatest culinary pleasures on

earth. But I hate fish and will never eat it.

Stan

finished explaining my “problem” to Marlene and why he was laughing to

Marlene who looked at me very strangely.

“No fish?” she asked.

“No fish,” I echoed.

The

deep seated aversion I had to fish was inexplicable. I had grown

up less than a quarter of a mile from New York Harbor, in Bay Ridge

which

is the section of Brooklyn that anchors the Verrazano Bridge. For the

first

ten years of my life a squat, green ferry crossed the narrows from the

69th street pier in Bay Ridge to Staten Island. The ferry went out of

business

when the bridge was finished in 1964, but the pier at 69th street was a

favorite fishing spot where all the neighbors would go crabbing on the

weekends.

I was

terrified by the sight of these mesh cages filled with living

breathing,

ugly, monstrous crabs. My uncle John would be one of the fisherman from

time to time and would take the crabs out their cages and chase after

with

me aiming the crabs for my throat. I had also just seen “The Creature

From

The Black Lagoon” which didn’t help my paranoia about biting into

things

that lived under the water.

In

the Joan of Arc nursery school one of the teachers tried to convince me

that the tuna salad she was serving me was actually chicken, but after

one taste I knew I had been lied to and became hysterical. Fish and I

would

never come to an easy agreement.

Dietrich

picked up the phone in her dressing room and dialed 411. “Get me The

Fisherman,”

she purred. Obviously the operator didn’t realize it was the great

Marlene

Dietrich when she asked. “What city please?

“I don t know what city, just connect me to The Fisherman. It’s a

westauwant.”

She

held the receiver for a moment while the operator found the number ands

then made the connection.

“Hello, Fisherman?”

I

swear I thought she was going to cut the reservation to 7 instead of 8

and let me sit in the car while they all had dinner. Instead she said,

“This is Marlene Dietrich speaking. I am coming to your westauwant with

a party of 8. One of my guests eats no fish. Does the Fisherman serve

meat?”

It sounded like an oxymoron. A meat-catching fisherman. She listened

for

a moment then nodded as though she understood the answer and hung up.

“There will be no problem. Shall we go?”

It

only took her a few minutes to change into her red pants suit and we

left

by the stage door. There was a crowd of about twenty waiting for an

autograph

or just a close up look at the great star, but she was like a tight end

pushing her way through the people, not stopping, not looking until she

was inside the back of the limo. The rest of us followed her in and

within

a few minutes we were being escorted into The Fisherman. The place

smelled

of fish.

The

maitre’d bowed and led us to a beautifully set round table in the

corner

overlooking

the wharf. Most of the people in her entourage didn’t want to sit next

to her, leaving me next to the legend who still looked like the icon

rather

than the old German lady. As soon as we got settled, Stan Freeman

noticed

a young girl approaching the table. She was heading straight for

Dietrich.

There was another great star eating at the restaurant that night and

she

had sent the girl over to say hello to Marlene on her behalf.

The

girl pulled up right next to Dietrich and said, “Excuse me, Miss

Dietrich.”

Without

turning or looking, Marlene said coldly, “You are not excused.”

The

girl went white but continued with her mission. “But I have regards for

you from Ann Miller. She’s sitting over there.” Dietrich looked across

the room to see Miss Miller waving to her then turned to the girl and

said,

“Ann who?”

“Ann

Miller,” repeated the girl.

“Well,

you are vewy wude. Now please leave this table.”

The

girl, almost in tears, ran back to the Miller table and whispered into

Ann’s ear. Miss Miller shrugged and everything went back to normal.

Stars

and public figures can be funny about fans interrupting their dinner.

There’s

a famous story about Rex Harrison having dinner with Moss Hart at

Sardi’s

between a matinee and evening performance of “My Fair Lady.”

Legend

has it that an elderly woman approached the Great Rex with a program in

hand. “Oh, Mr. Harrison,” she gushed, “you are my most favorite actor

in

the world. I’ve seen every film you’ve ever made I waited a year for

front

row seats to the show and there you were in person and I was breathing

the same air you were breathing and you are so handsome and talented

and

if only you’d sign my program my life would be complete.”

Harrison

turned on the lady and barked, “How dare you, you old biddy. Can’t you

see I’m trying to enjoy my dinner without you prattling on. I don’t

care

who you love or what air you breathe or anything else. You are

disturbing

me.”

With

that, the lady held off, smacked him on the head with her playbill and

walked away. Moss Hart then observed, “Well, that’s the first time I

ever

saw the fan hit the shit.”

I also

saw Pearl Bailey treat a young fan terribly. It was at Sardi’s after a

performance of “Hello, Dolly!” when a small boy of about ten approached

the star at her table. “I saw the show today,” said the lad, “and could

I have your autograph?”

Miss

Bailey sneered at the boy, “Can’t you see I’m eating with my friends.

Hasn’t

your parents taught you any manners? I’ll sign the program when I

finish

eating and you can just stand there until I do.” The boy started to cry

and stood frozen not knowing what to do. His mother ran over and

collected

him while Miss Bailey never looked up again.

The

mood of the dinner changed for the good when Joe Davies, Dietrich’s

lighting

designer, arrived with an early edition of the San Francisco Chronicle

that contained a rave:

Dietrich

and her act are the most remarkable feat of theatrical

engineering

since the invention of the revolving stage, and age has if

anything

reinforced her voice to the point where (for " Lili Marlene” or

Seeger's

"Where Have All the Flowers Gone ?") she seems to have within her the

strength

of entire armies.

While

we sat at dinner, I asked Marlene how Stan had come to be her musical

director.

She told me that when she first put the act together, Bewt Bachwach was

her conductor and friend, but he had tired of doing the show and was

preparing

his first (and only) Broadway musical “Promises, Promises.“ As things

are

meant to happen, Stan was walking down Fifth Avenue one night and ran

into

Bert who said Marlene was looking for a new conductor and he would

recommend

Stanley if he wanted the job.

Bert

warned him that she wasn‘t easy to work with, but Stan couldn‘t pass up

the money and the perks that came along with the job so he took on the

assignment.

The

first few weeks were rocky. Stan said she was impossible to work with

and

found fault with everything he suggested or did. After one performance

in London, Marlene complained about something Stan had done and he hit

the ceiling, calling her every name in the book. He told her she

couldn’t

sing and that she was overrated and a supreme pain in the ass to work

with.

She loved him from then on.

The

outburst did the trick. Marlene cried and said that she couldn’t lose

him

because he was the best conductor she had ever had. They were together

for twelve years until Stanley helped to end her career for good.

They

were performing at the Shady Grove Music Theatre outside Washington,

D.C.

On the first night, all went well except for the curtain call. Marlene

came over to the foot of the stage and reached down to shake Stan’s

hand

after the performance. He said that she had to bend so far that he was

afraid she would fall into the pit.

The

next night, November 14, 1973, the show went along fine - full house,

responsive

crowd and standing ovation at the bow. Stan, being a gentleman, decided

to stand on the piano bench so that Marlene wouldn’t have to reach down

as far to shake his hand. He stood on the bench, took Marlene’s hand,

the

bench broke and he pulled her into the pit. Miss Dietrich landed on the

drums, accompanying her fall with a tremendous, unexpected rim shot.

Blood

poured over her famous gown and it turned out she had gashed her leg

open

as she was impaled on the cymbal.

He

told me that the audience let out a group gasp and an elderly married

couple

who had been sitting in the first row leaned over the orchestra pit

railing

and very nonplused said, “Very nice show.”

An

ambulance took her the then 72 year-old to the local hospital where she

was stitched up but the doctor found it difficult to close the whole

wound

which was about four inches in diameter. Senator Ted Kennedy sent his

own

personal physician to assess her condition and he told her that she

lost

a great deal of skin which had been sliced off by the edge of the drum

kit.

Stan

visited her in the hospital and was truly heartbroken that he had been

the cause of her troubles. She said she didn’t blame him. It was an

accident

and accidents happen. Though she did mention that the pain was

unbearable

and she would have to go through months of skin grafts and physical

therapy.

She added that the doctors weren’t sure if the wound would ever heal or

that she would ever walk properly again but that Stan shouldn't give it

a second thought because it wasn’t his fault - though if he hadn't

gotten

on the bench, the accident wouldn’t have happened.

For

weeks after the accident, Marlene would send pictures of her leg with

horrific

pictures of her wound - before and after the skin grafts - and then

with

huge bandages that covered her legendary leg from ankle to knee. With

each

note and each picture, Dietrich underscored that it wasn’t his fault

and

he shouldn't feel guilty.

She

performed two weeks later in Toronto against her doctor’s wishes where

she saw no one outside of her group, traveled by freight elevator

between

her room and the stage and played the entire two hour show in enormous

pain. Her leg would not heal if she kept up the schedule so she knew

she

had to tend to her leg or it would be amputated. The leg that once had

been insured by Lloyds of London.

After

Toronto, she returned to her apartment in Paris where Stan would call

her

from time to time to cheer her up. Marlene always answered the phone

herself

but insisted she was the maid and that Miss Dietrich couldn’t come to

the

phone but she would pass on his good wishes.

Dietrich

eventually went back to work after about nine months of recuperation

and

brought Stan back to conduct for her. But she wasn’t the same. She was

brittle and in pain while she performed and took to using a stool so

that

she wouldn’t have to stand. Even the potassium from the bananas

couldn’t

help.

On

October 4, 1975, while she was performing in Sydney, Australia she fell

again without any help from Stanley and broke her leg. That was the end

of her career. She never performed again and she retired to her Paris

apartment,

a place she never left until she was carried out in feet first in 1994.

June

20, 1959 - New York City

How

does a kid from the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn go into show business

and get to watch Marlene Dietrich rehearse when all he ever wanted to

be

was a priest. I was born on August 16, 1946 in the first year of

the baby boom, the second year of the Truman presidency, the third

printing

of Dr. Spock’s The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care,

the

fourth sold-out month of Annie get Your Gun and the fifth week

that

Chiquita

Banana tied with Zip-a-de-Doodah in the top slot on Your

Hit

Parade.

Just

about everyone in my family - mother, father, grandmother, grandfather,

uncle and some cousins were born in August which led me to believe that

the Brochu-Condon-Ryan-Morrissey clans only had sex at Thanksgiving

whether

they wanted to or not. They were all so logy from all that turkey

that they fell into bed and did what came naturally.

My

father’s side of the family came from French Canada by way of upstate

New

York and settled in Washington Heights just south of the George

Washington

Bridge. My mother’s folks were from Ireland and settled in what was

then

called the Fourth Ward of New York Cty's lower Manhattan, an area along

the East River just South of the Brooklyn Bridge. My mother,

Veronica,

was an only child, the daughter of Dick Condon and Theresa Morrissey:

my

father - son of Joseph Brochu and Mary Ryan - was the oldest of three

boys

and a girl who died of cholera when she was four.

Mom

met dad when she worked in the steno pool for the Wall Street brokerage

firm Allen and Company where dad was an up and coming executive. He

started

as a runner there in 1933 where the patriarch of the Allen clan,

Charles

Allen, saw potential in my father and promoted him to Municipal Bond

trader.

He became enormously successful by raising bond revenues for projects

such

as the Mackinac Bridge in Michigan, the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel and the

Verrazano Narrows Bridge.

Mother Vera,

age 25 (1944) and a proof of Dad, Pete, age 25 (1937)

Mother

was, as my father described her, a “classy broad” who look like Merle

Oberon

and enjoyed a dirty joke with the best of them. They were engaged in

1937

but didn’t marry until 1943 while dad was on leave from his navy duty

in

the South Pacific. They pulled the wedding together in five days. My

mother

was never a well woman, having fought a bout of rheumatic fever when

she

was a child that left her heart weak. She died on Father's Day, 1949 at

the age of 29 when I was three years old.

My

father’s widowed mother moved to Brooklyn with her youngest son, my

Uncle

John, to live with us in Bay Ridge. The last thing a 60 year old woman

wanted to do was take care of a three year old boy, but she made the

sacrifice.

The only thing she and my mother’s mother Tess who I called "Ma" but

everyone

else referred to as "The Chief" had in common was their devotion to the

Catholic Church and the opportunity to mold me into being a priest. And

it almost worked.

Like

a career, I started as an altar boy and worked my way up to being our

pastor,

Bishop Edmond J. Reilly’s personal altar boy. The Bishop formed an

alliance

with my grandmothers by giving me the prime daily masses and making

sure

I watched Bishop Fulton J. Sheen instead of Milton Berle on Tuesday

nights

at nine. In fact when Bishop Reilly died in 1958, Bishop Sheen came to

Our Lady of Angeles in Bay Ridge to deliver the eulogy and I was

assigned

to carry his bags. Sheen was one of my idols but at age 12, I was

already

a few inches taller than the charismatic though diminutive evangelist.

The Brochu-Condon-Morrissey

Clan at my First Communion.

(l. to r.) Pa

and Ma Condon, Jim, Dad, Uncle John, Nana, Aunt Helen Quain,

Aunt Betty Morrissey,

Uncle Eddie and Aunt Jo Nash, Uncle Bobby Morrissey.

(How come nobody

looks happy?)

A few

months before Bishop Reilly died, I asked my father if we could go to

Europe

for the 100th anniversary of the Lourdes apparitions. I had seen “The

Song

of Bernadette” many times and wanted to see the locations for myself.

Dad

agreed, giving me many perks since I was an only child without a mother

and booked an entire “Catholic Pilgrimage” of Europe which included all

the great shrines of London, Paris, Brussels and Rome. The first stop

was

Shannon Ireland where I stopped the immigration process cold by stating

my profession as altar boy. There were two priest-chaplains named

Hewitt

who were real-life brothers from Tom’s River, New Jersey. They also saw

me as a future priest and bought me a black priest’s biretta which I

wore

all through the trip.

In

Lourdes, I expected to see a full blown miracle only to witness a sick

man fall out of his wheel chair and crack his head on the cement. The

viewing

of the mummified body of St. Bernadette proved more creepy than

inspiring

and the home in which she lived was far more upscale than the dank

prison

portrayed in the film.

The

pinnacle of the trip came in Rome where we attended an audience of Pope

Pius XII’s and I stood close enough to almost touch him. The presence

of

this living saint was marred when he opened his mouth to bless the

crowd

and he sounded like Gracie Allen with a bad Italian accent.

In

Paris, we visited every church in the city and met a Bishop Boardman

from

Brooklyn, who as fate would have it, would become my pastor after the

death

of Bishop Reilly. Boardman was a ruddy-faced politician who could have

been cast as a Senator as much as a prelate. When he did become our

pastor,

my father reintroduced himself and reminded the Bishop that we had met

and spent time with him in Paris only a few months before. Boardman,

ever

the glad-hander said, “Of course I remember you. I remember you very

well.

And how’s your lovely wife?” “Dead,” answered my father, “for ten

years.”

Pius XII's Audience

in St. Peter's Square (1958)

Yes,

as I entered the seventh grade it was all but decided that I would

enroll

in the minor seminary after graduation and take the first steps on my

sacred

path to being the first Brooklyn-born pope. And then my grandfather

bought

me a record player and that path was forever detoured. Pa, my

mother's

father, had bought the record player because I told everyone who

would listen that I had sent away for a record album of Pope Pius XII

singing

Gregorian chant but had nothing to play it on. The record player

arrived

before the pope’s LP and so I went to the record store and picked up

the

first album I saw - Ethel Merman in Annie Get Your Gun.

I raced

home to test the sound of my new phonograph and heard my first

overture.

Then came the voice of Merman. Oh that voice. Oh my God, that voice.

She

sang “Doing What Comes Naturally.” Before I got to the next track, I

replaced

the needle and played it again. And again. Within a half hour I knew

every

word. My grandmother who lived with me, who we called Nana, was going

out

of her mind. Finally she came into the bedroom I shared with her and

said,

“Turn that screech owl off!”

“Don’t you like her?” I wanted to know.

“No, she’s a loudmouth multi-divorcee,” came the reply.

I didn’t

know why my Nana had linked her singing power to her marriages and

didn’t

care about the connection. All I knew was that the voice inhabited

every

fiber of my body and perhaps had taken over my soul. After my

grandmother

went to sleep, I took the record player out to the living room and

listen

to the album all over again with my ear pressed against the speaker,

the

volume almost inaudible. My father came home with a half snootful, as

usual,

as asked me what I was listening to. Thinking it was permission,

I turned the volume up full and Merman’s voice inhabited the room. Dad

started singing along with her to “There’s no Business Like Show

Business”

and then said,“What a great show!”

“You

saw her?”

Came

the incredible response, “Saw her - I know her!”

“What do you mean you know her?”

“Her dad is the CPA for my company. Ed Zimmermann. He’s one of my best

friends.”

“Did you ever meet her?”

“Of course I’ve met her. I see her all the time when she comes down to

have lunch with Ed. I’ve even taken her out to dinner a few times.”

“Will she be my new mother?” I wanted to know.

“I don’t think so,” he said, “She’s married to the head of

Continental

Airlines. We’re not in the same league.”

“What does that mean, daddy?”

“It means I couldn’t afford her.”

“Nana hates her voice.” I offered.

“Well, she should hear her sing in person.”

“I want to hear her sing in person,” I said almost jumping up and down.

“Where does she sing?”

“She sings on Broadway. She’s in Gypsy.”

For

a moment, “in Gypsy” sounded like one word and very Latin - like the

pope

making a pronouncement “Ingipsie.”

“Can

we go see it?” I begged.

“I

don’t think you’re old enough.”

The

noise had awakened my grandmother who stood in the hall just in time to

hear me say, “But you took me to see naked women when we went to Paris

last year.” My Uncle John, the original couch potato, was suddenly

interested.

Nana

choked, “Naked women?! What are you talking about. What naked women?

What

is he talking about, Pierre?”

Though

my father was named Peter, Nana thought Pierre was a better first name

to go with our French Canadian surname. My father had learned to defend

himself all through grammar and high school every time one of the

toughs

yelled “Hey pee-in-the-ear” and dad almost killed my grandmother when

he

went to get his working papers and saw on his birth certificate that he

had been christened Peter., not Pierre.

“It was a harmless little nightclub,” my father tried to explain.

“With naked women? Jimmy, go to bed. Your father and I need to have a

good

talk.”

I did

as I was told and from the bedroom I could hear the argument continue.

While we were in Paris, dad had taken me to a smoke filled basement

dive

where a dozen women came on a small stage and took off all their

clothes.

I wasn’t sure about what was happening since the first one came out

dressed

in a cowgirl outfit looking very much like Dale Evans. It was the first

time I ever saw - as my father called them - “jugs” up close and

personal.

I was twelve, preferred looking at men, and yet I found myself with a

strange

tumescence.

Outside

in the living room, dad was trying to be respectful of his mother. He

tried

to explain that we had gotten there by accident because the joint was

next

to a church. I guess he didn’t see the huge neon sign that kept

flashing

on and off reading, “Le Club Sexy.” After a few minutes more, I

heard

him say to her, “Oh, be quiet and go to bed.“ Nana came in seconds

later.

I pretended to snore so that the conversation wouldn’t continue and I

wouldn‘t

have to answer any questions.

I called

my father at his office the next day and told him he had promised me to

take me to see Gypsy. I knew he wouldn’t remember. I had often used

that

trick to get what I wanted - knowing dad would never remember because

he

was sloshed the night before. “Okay, I’ll call Ed and get Ethel’s house

seats for the Saturday matinee - June 20th at 2:30 p.m.

Dad

invited my grandmother and Uncle John to go with us, but she invoked

the

Legion of Decency which had condemned the musical as being too prurient

for any catholic of any age to see. She would not go and she would not

permit her youngest child to go, even though he was 36 years old.

My

father gave the other tickets away to two actor friends of his, Matt

Tobin

and Otto “Babe” Lohmann. Ed Zimmermann, Ethel’s father met us in front

of the Broadway Theatre on West 53rd Street and handed us the tickets -

Ethel Merman’s own house seats, E 101-104. I sat on the aisle.

I had

actually seen one other Broadway show - a straight play - when I was

11,

do to my love of science fiction. I was home sick from school one day

when

I watched an afternoon interview show featuring an appearance by Cyril

Ritchard. Ritchard had played Captain Hook brilliantly in the

television

presentation of Peter Pan opposite Mary Martin, but now he was

promoting

a show called Visit To A Small Planet by Gore Vidal. I loved

anything

that had to do with space travel and so when my father came home, I

asked

him to take me to see it. He didn’t make the connection with science

fiction,

only proud that his eleven-year-old son wanted to see a Gore Vidal play.

The

show was at the Booth Theatre and I did not expect the lights to go

down

and to be in the dark before the curtain went up. I expected a

planetarium

show, but when the curtain rose we were in a suburban living room with

very earthly characters whose every other word was “bastard’ or” son of

a bitch. My grandmother, sitting next to me, jumped every time and

epithet

was uttered. The whole experience enchanted me but didn’t prepare

me for the transforming experience that was Ethel Merman in Gypsy.

As

we took our seats in the front row and listened as the orchestra tuned

up, there was a buzz of excitement that filled the theatre. It was like

church but with energy. The overture began, the trumpets blared, the

curtain

went up and Ethel Merman swept down the aisle right next to me

shouting,

“Sing out, Louise! Smile, baby!” By the time two hours had passed, I

experienced

a religious conversion the likes of which I had never felt in Lourdes

or

Rome. Visit To A Small Planet had been a three act play and I was

shattered

that the cast started taking its bows only after two acts. I didn’t

want

it to be over. It had to go on forever. And even though the show

had been condemned by the Legion of Decency for some inexplicable

reason,

the girls in the burlesque scenes still wore scads more than those at

Le

Club Sexy.

When

the house lights came on, my shaky legs barely got me out of my seat

and

carried me around the corner to the stage door where we were going to

meet

Mr. Zimmermann. He would then take us through to the backstage to meet

his daughter. The doorman told us that Miss Merman was on the stage -

waiting

for us. We could go right out. It was like walking onto holy ground.

She

was still in the same lavender dress she wore for Rose’s Turn, the

electrifying

finale of the show.

“Hiya,

pop!” said Ethel as she greeted her dad. “Hiya, Pete,” she said as she

gave my dad a kiss on the cheek. “And this must be Jimmy.”

Oh

my God, she knew my name. I could feel the stage hands swirling around

us putting the sets in order for the evening show but I couldn’t take

my

eyes off of Merman. My first thought was that she was taller than

Bishop

Sheen.

She

must have thought me to be an idiot because I couldn’t answer any of

her

questions. “Did you like the show?” “How were the seats?” “Have you

seen

a Broadway show before?” “What grade are you in?” And then, the curtain

of the Broadway Theatre went up and I looked out into the house with

its

rows of blue and gold seats and huge windows on either side of the

stage.

Then

came the question from Merman, “So what do you want to be when you grow

up?” I always had a ready answer to that question which I had been

asked

hundreds of times, “I’m going to be a priest.” But this time, I had no

answer except to stare into the empty Broadway Theatre and mumble,

“This!”

The

course of my life was forever changed that day. The road to Rome became

the road to Broadway and worship of the Virgin Mary was transferred to

the great Merm. I ended up seeing Gypsy a dozen times over the almost

two

years it played on Broadway and saw Merman every time after. She always

greeted me warmly. Always had time.

A few

years later, we had dinner with Ethel and her parents, Ed and Agnes, at

Toots Shor’s Restaurant on West 52nd Street. It was a sad dinner

because

Ed was going blind and Ethel had to cut his meat for him and help move

his food around the plate to find the pieces. Ed started crying, not

wanting

to be a burden to his family. He couldn’t work anymore because he

couldn’t

see the numbers in front of him - rendering him useless as a CPA.This

realization

seemed to hit at dinner with his daughter cutting his meat for him and

little Agnes holding back the tears watching.

Ethel

Merman and Me (1976)

Some

twenty years later, in 1981, I worked with Merman and cried when

I realized that she had experienced some kind of brain meltdown when

she

couldn’t remember the lyrics to a song she introduced in the 1930s. I

called

my friend Stan Freeman who had conducted for Ethel often and told him

about

the incident she had at the taping. “Getting old isn’t pretty,” he

said.

“If I ever get to that point, I think I’ll just end it all.” In January

of 2001, he did just that.

Stan

Freeman was my best friend for thirty years and I learned that one of

the

reasons Stanley was not a well-known name except for show business

circles

was that he did too many things too well. I believe Stan was one of the

greatest piano players of the 20th Century. His most famous gig was

playing

the harpsichord on the Rosie Clooney recording of “Come On A My House.“

He composed two Broadway shows. The first was” I Had A Ball” in 1964

with

Buddy Hackett which was a moderate success and in 1970, “Lovely Ladies,

Kind Gentlemen” which was one of the best known flops in the history of

Broadway.

Clive

Barnes review of the show caused the cast to picket him and the New

York

Times

when he wrote a scathing assessment of the musical beginning with “I

come

not to praise Lovely Ladies, but to bury it!” And he did. The show

which

starred Ken Nelson, Ron Hussman and David Burns, closed after limping

along

for two weeks.

The

funny thing about “Lovely Ladies” is that it wasn’t a bad show. Those

who

saw the show enjoyed it very much. It was not the greatest musical

ever,

but certainly not worthy of Barnes’s scorn. It was the wrong show for

the

wrong time. Nobody wanted to see the musical version of Teahouse of the

August Moon, about soldiers occupying the Japanese island of Okinawa,

while

the Vietnam war was raging on. All-Singing, All-Dancing Asians (played

by whites) wasn’t what the Broadway audiences were craving in 1971. But

I saw almost every one of the 16 performances because one of the stars

of the show was the man I loved. I had always been looking for another

mother, but in David Burns I found another father. I was holding out

for

Joan Crawford to be my mommie, dearest.

And

then came Crawford!

Me, Cathy Crawford,

Joan Crawford, Cindy Crawford, Dad

Bio

| Résumé | Current

Appearances | Video Clips | Lectures

| Jim's Books and Plays | Press

and Reviews |

Photo

Gallery | The Last Session

Homepage | The Big Voice: God

or Merman? Homepage | Contact

CHAPTER TWO: Latitudes and Attitudes

<><>July 1, 1960 - En Route to Rio De

Janeiro<>

Just

as our Bon Voyage party on the S.S. Brasil was peaking, dad’s

drinking buddy, Bill King, came lurching into the cabin to announce

that Joan Crawford had

booked space somewhere on the ship and was sailing with us. I had

no idea who Joan Crawford was but

everyone in the room was thrilled about it. Mr. King, who was

absolutely

bombed, suggested we go to Crawford’s stateroom and introduce

ourselves. I was

trying to keep an eye on my grandfather, Dick Condon, who was also on

his way

to total oblivion since he wouldn’t relinquish his seat in our cabin

and the other paartygoers kept

pouring scotch down his throat.

Dad

told me Joan Crawford was one of the greatest movie stars of all time -

an

Oscar winner - and suddenly I was interested. We formed a small welcome

aboard

committee, went down to the public room where Miss Crawford’s bon

voyage party

was in full swing and knocked on the door. After a moment, the door

opened and

there stood a beautiful lady in a black and white polka dot dress with

a huge

black picture hat framing her red hair.

I

only got a glimpse of her before Bill King stepped in front of me and

said,

“Miss Crawford, my friends are sailing with you and I just wanted you

to meet

them.” Joan said a hello to no one in particular and started to close

the door

as Bill King put one foot inside and said, “Miss Crawford, may I kiss

you.”

Without seeing the reaction on her face, all I heard was a soft, sweet

“No” as

the door closed. We went back to our party.

One

of the saddest things about the takeover of the terrorists these days

is the

demise of the bon voyage party on the great ships. Back in the sixties,

anyone

was welcomed aboard to celebrate the departure of their friends on an

ocean

voyage. For a fifty cent contribution to the Norwegian Seamen’s Fund,

the ship

was open to all visitors. Dad decided that we would go on a cruise the

summer

before I was shipped off to Military school.

The

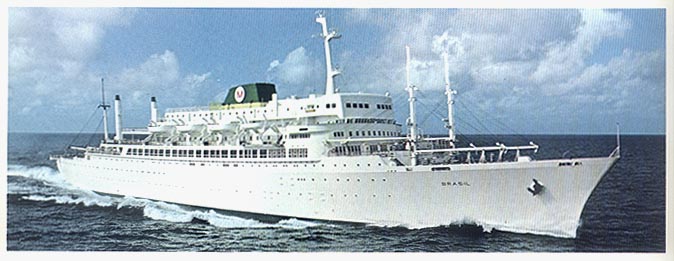

S.S. Brasil was the flagship of the Moore-McCormack Lines

which was half

freighter and half luxury passenger ship that made monthly voyages

between New

York and Buenos Aires with stops in Barbados, Caracas, Trinidad, Sao

Paulo, Rio

de Janeiro and Montevideo. Joan was not the only celebrity aboard. The

great theatrical

caricaturist Al Hirschfeld was also sailing with his wife, Dolly, and

daughter,

Nina, who he immortalized by placing her name in all of his artwork.

But Joan

Crawford was the only person my father wanted to get to know. And he

did.

Biblically.

The

announcement blasted through the stateroom, “All ashore that’s going

ashore.”

My grandfather tried to stand but couldn’t. The fourteen scotches he

put down

during the soiree had robbed him of his power of locomotion.

My

mother’s father was a fascinating man who started out as a fireman in

New York

City when horses drew the trucks through the streets. He won the James

Gordon

Bennett Medal for heroism, the highest honor the

Department could bestow on any of its fireman because he saved ten lives

during the infamous Triangle Shirt

Factory Fire in 191 But as we were preparing to sail, he was

sloshed and

incapable of movement. We propped him up against the door of the

stateroom and

told him to stand there as we found his hat and coat. When we turned

around, he

was gone.

We

panicked because the ship was about to sail and Pa (as we called him)

was gone.

Not in the passageway. Not in the elevators. Not on the decks.

Vanished. Dad

was about to make arrangements for him to go all the way to Rio with

us. The

Promenade Deck was lined with partying passengers, throwing streamers

and

confetti to their friends on the shore. We looked down the pier to see

if we

spotted Pa but he was nowhere to be seen. Then, as I looked down to an

opening

in the hull on the lower part of the ship where there was a conveyer

belt

bringing food on. It suddenly stopped and began rotating the other way

toward

the dock. Pa appeared on the conveyer belt supported by two crew

members

holding him under both arms and was rolled off to shore.

The

Brasil pulled out into New York harbor and began slowly

sailing down the

Hudson into the Narrows and passed the apartment house in which we

lived. We

didn’t sail under the Verrazano Narrows Bridge because it had not yet

been

built. I felt so lucky to live right on the Bay and I loved ships more

than

anything in the world. I would run to the roof early in the morning to

see the

new ships sail into the harbor on their inaugural call to New York, greeted by the fire boats spraying them with

a rainbow-infused welcome. I even watched the Stockholm limp

into the

harbor the day after it rammed the side of the Andrea Doria and

sank it.

The sight of the ship with its bow seared off was chilling, especially

after

watching the footage of the great Italian liner sink the night before.

The

first day at sea on the Brasil there was a mixer for all the

teenagers

on board so I went and met twin girls named Cindy and Cathy who were

exactly my

age . The cruise director, Danny Leone, hosted the party which lasted a

few

hours and made sure we knew the names of all the others kids our age on

board.

When the party was over, Cindy and Cathy invited me back to their cabin

to play

board games and I accepted. They wanted me to meet their mother, who

was

recently widowed. Always on the lookout for a new mother, I thought,

“Why not?”

When

we came into the cabin, their mother was sitting at the vanity table

dying her

hair. She greeted us all with a smile and welcomed a game of Scrabble

on the

stateroom floor. Within an hour, I knew I had found my perfect

stepmother along

with two built in stepsisters.

My

father didn’t want any part of it.

“But

daddy, she’s really beautiful!”

“I

know a lot of beautiful women,” he snarled.

“And

she’s a widow.”

“I

don’t want to meet any widows,” he confirmed. “And I don’t want to get

married

again. I’m not getting married again. So don’t do any matchmaking

because

you’re just wasting your time.”

Back

in the sixties, every night aboard a ship was a formal night with the

ladies in

elegant gowns and the men in tuxes. I always thought the guys had it

easy

because the tux was like a uniform - you didn’t have to decide what to

wear - a

tux was a tux - unless you had a white dinner jacket and then you had

to

decide.

Dad

dressed early and looked like a movie star in his formal clothes. He

went to

the Captain’s “Welcome Aboard” cocktail party early in hope that his

favorite

movie star would show up and he could wangle an invitation for a dance.

Alas, she was a no

show. I still hadn’t made the connection that Cindy and Cathy’s mom

with whom I

had spent the afternoon was Joan Crawford. When the waiter came in to

deliver

her ice bucket he only addressed her as “Mrs. Steele.”

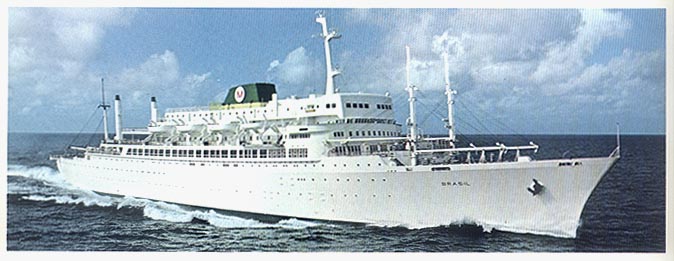

The Dining Room on

the Brasil. This was Joan's

runway to make an entrance.

Our

table in the dining room of the Brasil was all the way at the

back - a

table for two against the wall. Just after dad had ordered his cocktail

and I

was pondering a double order of mashed potatoes, a smattering of

applause began

to sound at the entrance to the room. The applause grew to a roar and

then a

standing ovation by everyone in the room. Dad saw her at a distance and

almost

spit out his Chivas.

“There

she is. Omigod. There she is. Isn’t she beautiful? God, she looks

great. Should

I go say hello. No. I’ll meet her later.”

Although

her table was

next to the Captain’s she kept coming right toward us. Dad looked

behind him to

see who she was looking at only to come face to face with the wall.

When he

turned back, she was standing right in front of us beaming, Cindy and

Cathy

demurely and properly behind her.

“Jimmy,

dear!” she started. “Don’t you look handsome in your dinner jacket?

Thank you

so much for spending the afternoon with us. What a good Scrabble player

you

are.” I looked to dad whose jaw was lying on the salad plate.

“And

this must be Pete,” she continued. “I’ve been hearing a lot about you.

Since

you work on Wall street, I’m sure we have many friends in common - and

we have

a whole month together to find out. Shall we have a cocktail after

dinner…and a

dance perhaps?”

If

you were to open a dictionary at that moment and look up the word speechless,

you would find a picture of my father. He could barely utter a sound as

he

shook her outstretched hand and nodded. The girls also put their white

gloved

hands out but my father never took his eyes off Joan as he shook them.

Even

tough I was only 13, I could not help but notice that there was a spark

between

the two of them. Joan looked back over her shoulder as the maitre’ d

led them

to their own table and she gave dad a wink which had the effect of

having his

legs pulled out from under him.

Dad in the foreground having dinner at

the Captains’s table on the S.S. Brasil

Knowing

Joan was experiencing my

first taste of what it was like to be a star.

On the cruise down the East Coast of South America, we made

stops at Sao

Paulo, Rio De Janeiro, Montevideo and Buenos Aires and at every port

the piers

were jammed with local residents trying to get just a glimpse of the

great

Crawford. The turnout was massive. Joan was there on Pepsi business and

scheduled a press conference for every stop. I couldn’t imagine how

many

steamer trunks she had brought since there was a new outfit for every

city, a

different dress for every day and she never wore the same evening gown

twice in thirty days.

On

the third night of the trip, my father did not come back to the cabin

until

morning. He woke me up at seven a.m. trying not to wake me up. I told

him I was

worried and went looking for him about three a.m. He told me he was

spending

time with a new friend. A few hours later, I ran into Cindy and Cathy.

They

couldn’t help me since their mother had a private bedroom in the suite.

Dad

didn’t show up for several nights and years later - after they stopped

seeing

each other and I was old enough to understand - he admitted to a torrid

affair

that lasted years after the ship returned to port.

After

Whatever Happened To Baby Jane? was released, I went to see

the film

with my best buddy from grammar school, Joey Maresca. I kept telling

Joey that

the woman who played Blanche was my friend and though he knew I had met

her on

the Brasil several years before, refused to believe that she

was indeed

my “friend.” Joan lived at 2 East 70th Street at the corner

of Fifth

Avenue which wasn’t far from where we had seen the film.

“If

you know her so well,” he challenged, “let’s go visit her.”

“Okay,”

said I, “Let’s go.”

It

was the middle of our Easter vacation and we were dressed, as my

grandmother

would say, ragamuffins. We got to the apartment door where the doorman

looked

down his nose at us and silently implied to just keep walking. Instead,

we went

up to him and I said, “We’d like to see Mrs. Steele please.”

“She

not home,” he barked.

“She

expecting us,” I lied. “And if she’s not home, Cindy and Cathy will be.”

He

looked at us quizzically, cocking his head to the side somewhat like a

beagle

that had heard a high frequency sound, and went inside. We could see

him on the

phone as he looked back and forth before returning with a somewhat

smile

drooping under his nose.

“She

said you could go right up.”

Joey

looked as astonished as the doorman as we were escorted - not to the

main

elevator - but to the service elevator in the rear of the lobby.

Joan’s

faithful housekeeper,

affectionately known as Mamacita was standing in the kitchen as the

elevator

door opened onto the small service hallway.

“Jeeeemy!”

she bellowed, enveloping me in her endless arms, “Missus is waiting for

you.

And the girls are here!” Then she added, “You know what to do!” Indeed

I did.

Before you could enter Joan’s apartment, you had to take off your shoes

to

prevent any outside dirt from creeping onto her pure white carpets.

Things got

off to a rocky start when Joey protested. I told him that was as far as

he went

if he didn’t. I couldn’t blame him. He shed his shoes to reveal a huge

hole as

with his big right toe sticking through it.

Mamacita

escorted us through the immaculate white living room into the

den/office where

Joan stood behind her desk, framed by a large picture window

overlooking Fifth

Avenue and Central Park. Cindy and Cathy sat on couches on either side

of the

room, giving the impression that the scene had been staged. The girls

were in

matching pink sun dresses and Joan was put together as though the

director was

about to shout, “Action!”

Joan

came around the desk and kissed me on each cheek. Cindy and Cathy

followed

suit. Joey was dumbstruck. The person we had just seen in Baby Jane

was

standing in front of him live and in person. Joan couldn’t have more

gracious

or welcoming, despite the fact that we were there uninvited.

“Thank

you so much for stopping by. The girls are home for Easter and you were

so kind

to think of us.”

“Joan,”

I started, “this is Joey Maresca. We just saw Whatever Happened to

Baby Jane?”

“I

hope you enjoyed it,” she smiled.

“It

was great,” we both stammered.

“Can

I offer you something to drink?”

Joey

answered first. It was an answer that sent chills down my spine.

“I’ll

have a coke,” he said.

The

girls’ eyes widened and they both looked at their Pepsi-wielding mother

for

guidance. Joan’s smile was implacable.

“I’m

so sorry, Joseph” she offered. “We don’t serve Coke here. Wouldn’t you

like a

Pepsi?”

Joey

winced. “No, I don’t like Pepsi!”

Cathy

actually gasped audibly but Joan continued to smile. “You don’t?”

“No,”

he said, “It’s too sweet!”

Still

smiling, albeit now a frozen smile, she offered a glass of water.

The

affair Joan had with my dad lasted about a year but my friendship with

Joan

endured until she died. From time to time, I would go up to the

apartment and

“hang” with Joan, still looking for the mother I had never known. Once

I went

to see her and this time she was actually expecting me. I even got to

go up via

the front elevator. When the door opened onto the foyer into the living

room, a

little old lady in a pink housecoat and babushka was waiting for me. I

said,

“Hi, I’m here to see Joan.” She stared at me with a half-smile,

half-frown and

said, “I don’t look that bad, do I?” We went into the kitchen

where she

was making bouillabaisse for a dinner party the next night - chain

smoking and

sipping vodka. The television was on in the background and a pizza

commercial

came on.

“What

fun it would be to just go out for a pizza.“ she sighed.

“Come

on, “ I said. “Let’s go for a pizza!“

“I

can’t. It would take me an hour to get ready.“

I

know I looked at her not understanding because she continued, “Don’t

you know I

can’t leave this house unless I’m Joan Crawford - and besides, you

don’t need a

pizza.”

Years

later, I became very close with Lucille Ball, who was just the

opposite. If the

urge for a pizza came over her, she would throw on some lipstick and

out the

door we’d go.

From

the very first time I met Joan she was on me from the start that I was

way too

fat and had to lose weight. This was to be an ongoing struggle lasting

for

years - within myself and with Joan. Almost every letter I (or my

father) got

from her over the years addressed the “problem.” For example:

August

19, 1964

Pete

darling,

I am

distressed with the news about Jimmy’s weight - my God, fifty pounds. He must get on a diet. Send him to Dr. Jerome

Klein at 1 East 69th Street, will you? He was very helpful

with

Cindy who weighs 164 now and should weigh 124. But Cindy has refused to

work

with the doctor and he has refused to work with her until she gets down

to at

least 155. Herbert Barnet’s niece went to Dr. Klein and she has trimmed

herself

down into the most beautiful young lady you ever saw. Have Jimmy

checked

thoroughly before you send him, naturally, but it would be a good idea.

It

would give him something to do and a responsibility of his own.

Joan

In

1966, when I was 20 years old, I wrote to Joan seeking guidance about

what to

do with the rest of my life. My father wanted me to study law and

follow in his

footsteps on Wall Street, but I had fallen in love with show business

and was

very influenced by Davy Burns. I wrote to Joan and even in trying to

give me

advice about my career path, she still managed to pick on me for being

overweight.

March

10, 1966

Jimmy

dear,

How

nice it was to receive your newsy letter. It’s interesting that you’ve

done so

many things in such a short time, but I think now, at twenty, you had

better

settle down into something you’re really going to do. You know that I

am your

friend at all times, but I must tell you that even though you are six

feet

four, 200 pounds is too much weight for you. But I am extremely proud

that you

lost 55 pounds.

You

mentioned that you are trying to do what your father wants you to do.

You’ve

always been very close to him. I think

he’s right and I think that Davy Burns is right - show business is

rough. There

are very few who make it like Davy Burns. It takes discipline beyond

belief and

work, work, work. Of course the other jobs you’ve been seeking take

discipline

too, but not nearly as much as acting. The other jobs you’ve been

seeking

require perhaps more knowledge college-wise. Acting requires knowledge

of

people and understanding of people.

I am

going off on a business trip for Pepsi-Cola tomorrow, but will be back

in New

York around March 20th. If you would like to come up and

have a talk

with me, I would be delighted to see you again. Or you may surely call

me on

the telephone. My number is still Murray Hill 8-4500.

Bless

you and have a nice talk with your father, okay? And I am always here

if you

need me.

Love,

Joan

April

5, 1967

Jimmy

dear,

Loved

your letter but am so sad to hear that your weight is still a problem.

Do take

care and my love to you and your father.

Joan

February

13, 1968

Jimmy

dear,

How

wonderful you have lost all that weight! I’m so proud of you. As you

said,

after getting over the first big hurdle, the rest should be a breeze.

Stay with

is now. God bless and my love to you and your dad.

Joan

November

29, 1968

Jimmy

dear,

I’m

delighted you’re maintaining a B average at school but do push a little

for

some A’s! It’s too bad about your weight. Be a good lad and push away

from the

table while you’re still hungry, Jimmy dear - that’s the secret of

dieting. And

no between meal eating of any kind and no bread, butter, potatoes or

deserts

(sic).

All

love, Joan

While

Joan was concerned about my dieting, she had the kind of fast

metabolism that

precluded her from gaining even an ounce. Mine was, and is still slower

than

Lincoln Tunnel traffic at rush hour. In the course of my life I have

gained and

lost the weight of the Taj Mahal.

Joan

gave me so much of herself in the seventeen years we were friends and

she also

gave me one of the greatest memories of my life - meeting President

John F.

Kennedy.

In

late October, 1963 Joan called and asked my father to escort her to an

affair

at the New York Hilton where the President was to receive an award as

father of

the year from the Protestant Council of America. I would be home from

military

school and was also invited to go. The grand ballroom of the Hilton was

packed

and in the next room was a dinner for the Catholic Actors Guild

presided over

by actor Horace MacMahon and filmdom’s “Blondie,“ Penny Singleton.

What

surprised me most about the evening was the lack of security. Our table

was in

the back while Joan sat on the dais near the president. People from all

parts

of the hotel just ambled in to get a glimpse of Kennedy and no one

stopped

them. I even walked from the back of the hall down to the stage to get

a closer